Inspiring Quotes Posts on Crowch

27 years in prison. Not for violence. Not for crime. But for a dream — of a nation where skin color didn’t define destiny.

Under apartheid, South Africa was torn by systemic racial oppression. Nelson Mandela, lawyer, activist, and co-founder of the ANC’s armed wing, fought for the freedom of his people — and paid with his freedom.

But what truly made him extraordinary was not just his struggle — it was his forgiveness.

Released in 1990, Mandela could have called for revenge. But instead, he chose peace. In 1994, he became South Africa’s first Black president — and used his power not to divide, but to heal.

“No one is born hating another person... If they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love.”

Mandela led with wisdom, humility, and grace. He created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission — to allow wounds to be spoken and healed, not buried. He embraced former enemies, taught unity, and showed that strength is measured not by dominance, but by dignity.

His legacy lives on — not just in South Africa, but in every place where peace is chosen over revenge.

Long before he became a symbol of peace and perseverance, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was a young boy herding cattle in the rural village of Qunu. Raised in the Xhosa tradition, he was taught values of respect, responsibility, and resolve. But the laws of apartheid South Africa would not respect those values — they would suppress them, reducing Black citizens to second-class status in their own homeland.

Mandela’s journey to resistance began in the courtroom. Trained as a lawyer, he believed that change could be achieved through legal means. But as the apartheid regime tightened its grip — banning political activity, silencing dissent, and enforcing racial separation with brutal efficiency — Mandela and others in the African National Congress came to a painful conclusion: peaceful protest alone was not enough.

In 1961, Mandela helped co-found Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”), the ANC’s armed wing, committing acts of sabotage against government infrastructure — never targeting people — in an effort to wake the world to South Africa’s injustice. For this, he was arrested, tried, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

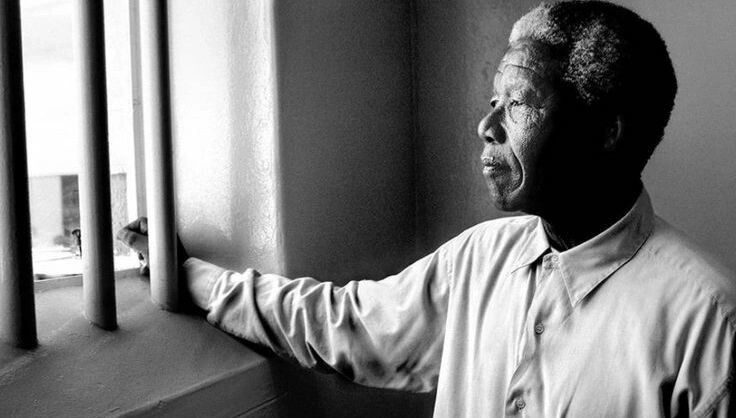

He would spend 18 of those 27 years on Robben Island, confined to a small cell, breaking rocks in a limestone quarry. But the prison bars could not contain his influence. He became a symbol of moral resistance, a figure whose name was whispered across continents — on university campuses, in protest songs, and within the chambers of the United Nations. “Free Nelson Mandela” became not just a slogan, but a demand for a different world.

In prison, he read constantly, meditated deeply, and forged bonds with fellow inmates and even some guards. Over time, he transformed from a political prisoner into a statesman in waiting. When negotiations to end apartheid finally began in the late 1980s, Mandela was not broken — he was prepared.

Upon his release in 1990, he stepped into a South Africa on the brink — torn by racial violence and fear. But Mandela’s first message was not one of vengeance. It was a call for peace, inclusion, and forgiveness. The world watched in awe as he shook hands with those who once called him a terrorist.

In 1993, he received the Nobel Peace Prize alongside then-president F.W. de Klerk. A year later, in South Africa’s first fully democratic elections, he was elected president. But power did not change him — it revealed him. Mandela chose to serve only one term, believing true leadership was not about clinging to office, but about creating institutions that could endure.

He invited his jailers to his inauguration. He wore the jersey of South Africa’s mostly white rugby team, the Springboks, during the 1995 Rugby World Cup — using sport to bridge a fractured nation. These gestures, while symbolic, had profound psychological impact: they showed South Africans that reconciliation was possible, that healing did not mean forgetting, and that unity was not naïve, but necessary.

Mandela once said, “As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison.”

That philosophy would define the rest of his life.

In retirement, Mandela continued to fight — for HIV/AIDS awareness, for global human rights, and for children’s education through the Nelson Mandela Foundation. He became a voice of conscience not only for Africa, but for humanity.

When he passed away in 2013, the world didn’t just mourn a leader — it mourned a moral giant. Presidents, poets, and schoolchildren alike paid tribute to a man who had walked through fire and emerged not with fists raised, but with open hands.

Mandela taught us that courage is not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. That freedom is not just political, but deeply personal. And that real leadership requires humility, empathy, and the willingness to forgive — even when it hurts.

His life remains a guiding light for all who seek justice without hatred, and peace without compromise.